Liam Neeson had a message for Seaview Primary School in the small coastal village of Glenarm Northern Ireland.

“I’m delighted to say that Seaview is just one of a number of schools that has conducted a democratic ballot of its parents since the ‘Integrate My School Campaign’ was launched just a few years ago,” Neeson said.

The school made headlines last month when it became the first Catholic school in the region to integrate, meaning it will teach Protestant, Catholic, and children from other religious backgrounds this upcoming September.

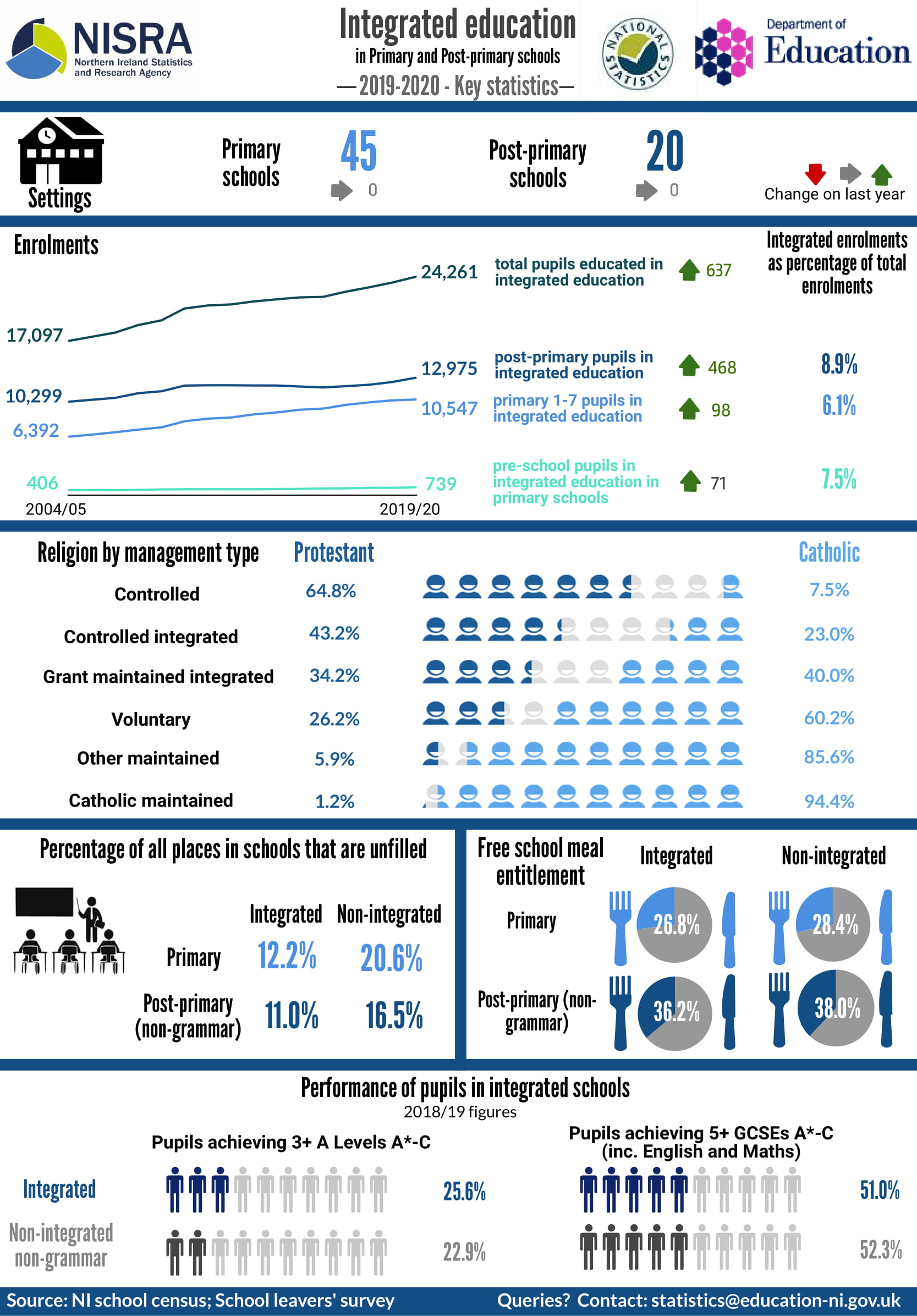

More than 20 years after a peace deal ended the sectarian violence known as the Troubles, Northern Ireland remains a deeply divided region and education is no different. Less than 10% of Northern Ireland’s students were enrolled in integrated schools during the 2019-2020 school year, according to a study performed by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.

But Neeson and the Integrate My School effort hopes to change that one program at a time.

The path of integrated education in Northern Ireland relies on parental demand, said Emma Hume of the Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education.

“We rely very heavily on parents because unless parents shout and cry and cause a fuss about not getting an integrated school place it’s harder for us to get school places,” Hume said.

While the council aids schools that want to become integrated, according to Hume, parents still need to take that first step of expressing an interest. This involved the council reaching out to parents at community events and having schools pass out electronic forms asking parents to talk to their principals about considering integration or signing an expression of interest form.

Hume said she has seen the benefits of integration first had. She grew up in a mixed marriage. Her mother, a Protestant, and her father, a Catholic, married at the height of the Troubles. While Hume didn’t attend an integrated school, she and her husband sent both of their children to an integrated primary school.

“We think it is the right thing to do for this country. It’s the right thing to help facilitate peace and reconciliation. We shouldn’t be segregated based on our religion.” Emma Hume, Development Officer at NICIE

“We think it is the right thing to do for this country. It’s the right thing to help facilitate peace and reconciliation. We shouldn’t be segregated based on our religion,” Hume said.

However, the legacy of generations of religious and political divisions can still be found in almost every classroom in Northern Ireland.

Groups like the Integrated Education Fund and celebrities like Liam Neeson have pushed parents, schools and communities to demand integration, but their effort faces a daunting history of divisive and costly failure.

Unlike the United States, education and religion have never been separate in Northern Ireland. As far back as 1831 British authorities proposed creating national schools that were non-denominational.

But according to Vani K. Borooah and Colin Knox’s book “The Economics of Schooling in a Divided Society,” the proposal prompted the Church of Ireland and the Roman Catholic Church to exert control over schools.

When Northern Ireland broke off from the rest of the island in 1921, the leaders of the new Protestant-leaning government responded to popular pressure to ensure that the ‘state’ schools were essentially Protestant, according to scholars. The Catholic Church responded by maintaining its own schools.

At the time, the majority of people living in the regions were unionist, in favor of remaining a part of the UK. Many unionists were also Protestants while nationalists, who favored a union with Ireland, tended to be Catholic.

Throughout the Troubles, from the late-1960s through the mid-1990s, political violence between the sides ensured little effort to integrate education, but several key groups sought to fight the segregation of education.

The Council for Integrated Education was founded in 1987. The council coordinated the development of integrated education and supported parent groups through the process of opening new schools. At the time, there were seven new integrated schools.

The Education Reform Order of 1989 mandated the Department of Education promote integrated education. It was the first time the government committed to support initiatives for the development of new integrated schools. This included providing funding for the Council for Integrated Education and other organizations like it.

Despite the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, schools were still a source of conflict. In 2001 violence flared at Holy Cross, a Catholic all-girls school in the middle of a Protestant neighborhood in Belfast. This included throwing stones at students and their parents as they walked to school. Riot Police and the British Army lined the streets in order to protect them. The violence died down after several months, allowing students to walk without a police escort.

Some people believe integrated education will lead to an increased understanding between Protestants and Catholics and perhaps prevent future events like Holy Cross.

John Brewer, who studies conflict and the aftermath in Northern Ireland, said that children who are educated together are less likely to be socially separate.

Kim Montgomery, a graduate from Queen’s University who grew up on the eastern coast of Northern Ireland, agrees.

“I had never even heard of the Gaeltacht [weekend trips away where high school age children learn the Irish language] until a boy I dated at university mentioned it, and he was astonished that I had never heard of such a fundamental experience in Catholic education,” Montgomery said. “If we had integrated education, the myths and anxieties each side has about the other would not have such a strong power.”

The Department of Education does not force students to attend integrated schools. But it does work with parents who want their children to attend integrated schools. And in addition to the the societal benefits, many point to the financial realities facing schools.

71,000 desks were unfilled in 2015. Department of Education: Sustainability of Schools Report

The Education Authority’s chief executive, Gavin Boyd, said nearly 400 schools operated at a deficit in 2017. There were 71,000 unfilled desks in 2015 according to a report on the sustainability of schools in Northern Ireland.

While some areas, like East Belfast, have more applications for enrollment than they have seats, many rural schools have the opposite problem.

Seaview Primary school was undersubscribed, meaning there were more places available in the school than children to fill them. Seaview was marked for closure by the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools due to low enrollment. The school then looked into how integration could boost their enrollment numbers.

The school lies in the shadow of the Church of the Immaculate Conception overlooking Irish Sea. A pale statue of the Virgin Mary is visible from some of the school windows.

It is one of four primary schools in the area serving a relatively small community. While transforming into an integrated school did double the enrollment, it is too low for the school to be considered financially viable in the long run.

The Department of Education and Council for Integrated Education has responded to issues like this through a policy called Area Planning. The policy was created to coordinate efforts to create educationally and financially sustainable schools.

According to Hume, this could mean that the Department of Education closes Seaview as well as the three other primary schools and creates one centralized integrated school for the area.

While Seaview Primary is a big step forward for integrated education, it is still owned by the Catholic Church, which creates a unique situation that previously integrated schools haven’t faced.

“This will almost be like a pilot case,” Hume said. “How do you do this? How does it work?”