When Amy-Louise Merron found out she was pregnant in her last year of prep school in Northern Ireland, she decided she would get an abortion. It was hard, and her options were limited to illicitly getting abortion pills from an aid group or taking a ferry to England.

In the end, and thanks to her family, she chose not to terminate the pregnancy.

But the experience made Merron, now a mother of two, a pro-choice activist in a country that had maintained its criminalization of abortion 50 years longer than the rest of the United Kingdom.

She was beginning her psychology degree at Ulster University when Northern Ireland decriminalized abortion in 2019. That day Merron drove to Derry to celebrate. “It was just really jarring to feel that sort of feeling,” she said. “Like, ‘Oh, my goodness. We have finally done it.’”

Prior to 2019, Northern Ireland had some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the western world, with women facing the threat of criminal charges for possessing abortion pills, and doctors facing similar consequences for performing the medical procedure. Abortions were only allowed in life-threatening situations. Even in cases of rape, incest or fetal abnormalities, women would legally be forced to carry to term.

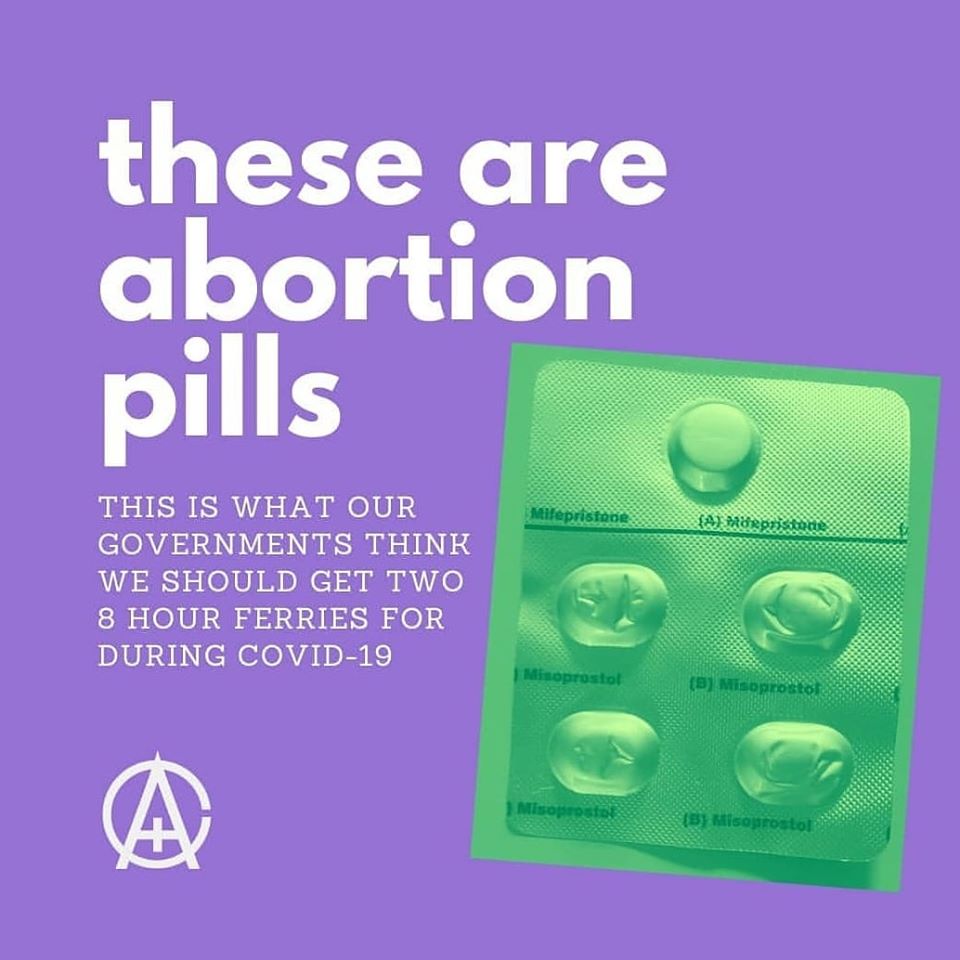

For decades, Northern Irish women quietly received shipments of abortion pills or traveled eight hours by ferry to England, partially funded by activist and aid networks like Women Help Women and Women on Web, to find an abortion.

They returned to their neighborhoods, and many of their neighbors chose to look the other way, silently.

And then, with pressure from Northern Irish rights groups, courts and the Parliament at Westminster, the British government set a deadline of October for Northern Ireland to decriminalize abortion. When the date came, the Northern Ireland Assembly had not met in more than two years. And so, the 1861 law that criminalized abortion was repealed. The new law allows Northern Irish women to receive a medical abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, with exceptions if there is a risk to the woman’s physical or mental health.

It was just really jarring to feel that sort of feeling. Like, ‘Oh, my goodness. We have finally done it.’” Amy-Louise Merron

Now, almost two years later, Northern Ireland continues to grapple with the rollout of a law still opposed by many lawmakers and stigmatized by parts of Northern Irish society. And as COVID-19 and Brexit threaten to disrupt clinic and prescription access, the path to abortion services remains difficult to impossible for most women in the region.

Dr. Fiona Bloomer, an abortion policy researcher and founding member of the Reproductive Health Law and Policy Advisory Group, has immersed herself in the world of abortion access for the past 10 years. Throughout her research, she said she found the biggest roadblock abortion access faced was Northern Ireland’s culture of stigmatization of the topic.

“It would be rare to talk about abortion, particularly pre-2019,” Bloomer said. “I was in conversation with people and they would say, ‘Oh, what are you researching?’ And I would say abortion policy, and there would just be a tumbleweed moment, because people didn’t know what to say in response to that.”

That is not to say that the Northern Irish did not have opinions on it. The year before decriminalization a survey from ARK-affiliated Northern Ireland Life & Times found that 85% of its 1,200 participants agreed abortion definitely or probably should be legalized.

The issue wasn’t whether or not people in Northern Ireland supported abortion legalization. The issue was that they didn’t want to talk about it.

Bloomer attributes the anti-abortion social stigma to a variety of factors, but primarily the intensity of religious views and the lack of sex education. Without public conversation, Bloomer said the abortion stigma kept people silent.

“There was always this fear of, ‘I don’t know how to talk about it, and I don’t know what you’re gonna say about this, so I’m afraid to actually give my opinion on it,’” Bloomer said. “So, there were a lot of people really, really hesitant about coming out. So, we had a lot of very, very quietly pro-choice people.”

Although society was quiet on the issue, Northern Ireland’s abortion laws have repeatedly drawn international attention and sparked protests. In 2016, a Northern Irish woman was reported to the police by a housemate and charged for owning abortion pills. In June 2019, a mother was charged and faced trial after procuring abortion pills for her teenage daughter.

The story was similar for decades in the Republic of Ireland until 2018, when Savita Halappanavar died from septicemia in a Galway hospital after being denied emergency abortion care for a miscarriage. The doctors told her they wouldn’t perform the abortion because Ireland was “a Catholic country.”

Within months, the Republic of Ireland voted to repeal its Eighth Amendment and legalize abortion.

Halappanavar’s death rippled into Northern Ireland, and along with conversation sparked by Northern Irish abortion court cases, the Northern Irish Assembly at Stormont faced rising pressure to amend the still-active 1861 Offenses Against Persons Act.

But Stormont wasn’t there. The assembly collapsed in January 2017 due to policy disagreements. They wouldn’t return until January 2020.

“I think I got pregnant and had a baby in the time that Stormont was down,” Merron said. “It was quite a long time.”

With Stormont out of session, Westminster stepped in to push through abortion access legislation, along with same-sex marriage equality, citing the bans’ incompatibilities with the UK’s humans’ rights commitments and European Union laws.

Merron, the founder of Ulster University’s first pro-choice society, now volunteers with Alliance for Choice, the leading non-profit pro-choice organization in Northern Ireland. Before decriminalization, Alliance for Choice helped support women in need of an abortion, both mentally, with crisis hotlines, and financially, with trips to England to get a procedure.

Merron feels strongly that talking about abortion is the best path to end the social stigma and increase access in the country.

“For me, personally, getting involved [with Alliance for Choice], it was the idea to be the voice on the other end of the phone,” she said. “To say, “You’re not alone. There’s other people going through the same thing as you. Do not feel like you have to do this yourself.’”

Image: @a4cderry

Now, Alliance for Choice is leading the charge to not only enforce the decriminalization, but also push for more tangible access to abortion services throughout Northern Ireland. Because conservative-leaning Stormont is back in session, and some lawmakers never wanted legal abortion access to begin with. They just weren’t there to try and stop it.

One of those lawmakers also happened to be Northern Ireland’s Minister of Health. Robin Swann, has historically identified himself as “pro-life,” and is the key minister to be in charge of abortion access rollout. Something the region has been slow to do.

Ten months after the Assembly reconvened, an open letter signed by over 76 organizations, individuals and legislators, including Alliance for Choice, Doctors for Choice and Northern Irish political party Sinn Fein, publicly called on Swann to roll out abortion provisions and guidelines.

After the publication of the letter, Swann’s office released a statement denying the Department of Health’s responsibility to commission services, stating only that “registered medical professionals in Northern Ireland may now terminate pregnancies lawfully.”

Abortions were no longer a criminal offense, but that didn’t necessarily mean they needed to be accessible.

By early 2021, the human rights group Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission sued the country over lack of attainable abortion services.

Again, Westminster stepped in.

“Almost a year has passed since the Abortion Regulations came into effect,” the British government’s Northern Ireland Office said in a statement. “We have reached a point where it remains clear that the Department of Health will not move forward to make positive progress on this matter.”

The British Parliament has granted Northern Irish Minister Brandon Lewis the power to bypass the Department of Health’s legislative path to fast track real, attainable abortion access.

“Not every abortion is a crisis situation. Not every abortion has to be a panic and a crisis. It can be quite an empowering experience.” Amy-Louise Merron

Though the path to legalization continues to prove itself tumultuous, pro-choice activists can say these changes, while mostly imposed by London, are changes nonetheless.

But still Merron and Dr. Bloomer think the best way to create actionable change is to destigmatize the still-controversial procedure in conservative Northern Ireland by starting a conversation.

“I think we spend a lot of time talking about abortion in a political sense,” Merron said. “But I think we really forget about the woman and pregnant persons themselves.”