The EU has been good for Declan Gormley.

Gormley, managing director of Belfast-based ventilation manufacturing company Brook Vent, spent the last decade expanding the company’s reach. Where Brook Vent once sold only one product and only in the United Kingdom, Gormley grew the business to its status today, exporting over 73% of its multiple products into the EU and beyond.

“And that’s been possible because we were in the European Union,” Gormley said, explaining that businesses on the edge of Europe, like Northern Ireland, would find it extremely difficult to enter a market country by country. “The EU afforded me the opportunity to set up in Poland as easily as I could do in Peterborough, England.”

Then the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, disrupting the economic security of many Northern Irish businesses like Brook Vent that had come to rely on the free access to an EU and UK market.

Photo: Contributed

Saying the UK was leaving the EU was much easier than actually leaving it. For years after the 2016 vote to leave (a move the majority of Northern Ireland voted against), hammering out a trade arrangement was a tedious affair that saw multiple proposals come and go. Northern Ireland, Britain and the EU agonized over various potential regulations for the only shared land border between the UK and EU. Three ideas were proposed, each progressively less strict.

Finally, a deal was struck. When Great Britain left the EU single market on Dec. 31, 2020, Northern Ireland remained. This meant the region could still export freely, anywhere, to both the EU and Great Britain. Imports, though, would prove to be a bit more complicated. To prevent products from sneaking into the EU through England, Scotland or Wales, a series of regulatory measures were implemented to deny third-country smugglers access to the EU through the back door of Northern Ireland.

But facing a series of export and import rules, most of which were delayed in March, many Northern Irish businesses have begun to reorganize their supply chains, turning to their own in-country products and the European Union, specifically through their southern neighbor, the Republic of Ireland. Because Northern Ireland remains in the EU single market and faces increased restrictions importing from the UK, some worry businesses will be the leaders in distancing the country from its British partners.

It’s too difficult, I’ll either find myself a supplier of the island of Ireland or I’ll find myself a supplier in France or Italy or whatever, they’ll be able to send the goods here without any delays. Declan Gormley, Brook Vent

“I think the real, immediate impact might be, if you find it difficult to import your raw material from the UK, then I think you will just switch your supply line,” Gormley said. “You will say, you know, ‘It’s too difficult, I’ll either find myself a supplier of the island of Ireland or I’ll find myself a supplier in France or Italy or whatever, they’ll be able to send the goods here without any delays.’”

Gormley himself has only had one significant glitch since the UK officially left the EU, with the importation of a product from one of his British suppliers. Aside from that, he’s seen relatively no change.

Photo contributed

That’s not to say he too hasn’t noticed the empty shelves in supermarkets or the lines of products being held up at customs, but rather that his last decade of work expanding the company into the EU paid off. With his pre-existing base in the EU, specifically Poland, he didn’t have to frantically search for places to re-source products.

“So, I think in practical terms, what the short term might be, because I’m doing it, is if you have one or two things that you can source in Poland, for example, where I have a base — but I might have previously been buying from the UK — I’ve just decided, why wait to see if there’s a difficulty here? I’ll just bring it in from Poland,” Gormley said. “Because you don’t have any restrictions, you don’t have any protocol, you don’t have anything. We’re allowed to import from Europe just as we were previously. So that’s the easiest thing to do.”

Richard Hogg, director of wind turbine manufacturing and repair business Precision Gear Company, runs his organization from its home base in the village of Toomebridge. While nearly all of his steel comes from Great Britain, most of the ingredients for his concrete — one of the biggest markets for Precision Gear Company — are sourced locally.

Like Gormley, aside from a few expected delays, Hogg hasn’t faced many challenges from the new Brexit regulations. He’s heard stories of those impacted, though.

“A lot of our UK suppliers are a bit miffed with [the new regulations],” Hogg said. “It’s slowing the process down a little. Some of my colleagues’ [suppliers] won’t supply to Northern Ireland, they say it’s not worth the hassle.”

Some of my colleagues’ [suppliers] won’t supply to Northern Ireland, they say it’s not worth the hassle. Richard Hogg, Precision Gear Company

In response, companies in his industry are turning inward.

“I think what quite a lot of the guys are doing, is they’re purchasing from the Republic, because there’s less paperwork,” Hogg explained. “It’s going to be easier to trade with Southern Ireland than, in some cases, with the UK. In the meantime.”

“You’ve gotta keep the stuff running, and you’ve gotta get your product from wherever you have to get it from,” he continued. “So if it’s more convenient to get it from the Republic, from Europe, than that’s what we’re doing.” Hogg didn’t see this being a long-term solution, but rather a short-term reaction.

Stephen Kelly, director of Manufacturing Northern Ireland, said the long term looks good for companies he represents.

“As of today, we have the ability to trade in both the UK and the EU without any customs, any tariffs, any barriers to those trades in our outbound direction. No other place in the world can do that,” Kelly said.

The keyword, though, is ‘outbound.’

“That does come with problems. So, our outbound is fine, we can just make stuff, put it on a lorry, put it on a truck, put it on ferry — a boat across to Great Britain. Problem sorted,” Kelly said. “However, stuff coming from Great Britain into Northern Ireland has to go through customs formalities. And that’s where the political conflict is at the moment.”

With much more industry and population, much of Northern Ireland businesses came to rely on British suppliers. Brexit and the Northern Irish Protocol complicated that.

Photo contributed.

“Because the UK has decided — in the first deal ever in the world to make trade more difficult rather than easier — to put barriers in the way of that trade, the UK’s position as a center of distribution is completely undermined,” Kelly explained. “What we’re experiencing is partly a reorientation, people are choosing different routes. What our guys are doing is, instead of getting goods from Great Britain, they’re getting them directly from Europe.”

That is easier when Europe is just down the A-1 from Belfast.

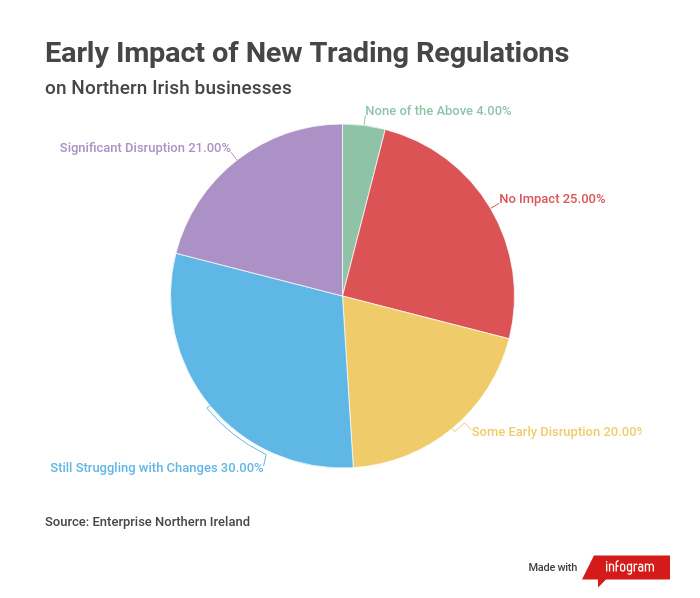

And the uncertainty that accompanied a last-minute trade deal has pushed companies to look to Europe. Michael McQuillan, chief executive of Enterprise Northern Ireland, a trade group helping small businesses as they look to expand internationally, said companies he talks with are struggling with the change.

One survey, conducted in mid-February, which focused specifically on 133 local businesses that trade goods to and from Great Britain, found that 36% of the businesses reported their UK-based suppliers were not prepared for the new processes. Another 30% reported that their British suppliers had indicated they were going to stop shipping to the region.

The same survey found that 19% of businesses had already localized their suppliers to either Northern Ireland or the EU. Another 22% indicated they were actively investigating a similar transfer.

“So, they’ve home shored [supplies] or gone into the EU to get those supplies,” McQuillan said. “And a lot of that is just to the south of [Northern] Ireland, you know, 50 miles down the road is the EU. And there are no trade barriers there at all. So that’s an interesting shift.”

Overall, McQuillan, Kelly, Gormley and Hogg saw the potential for a shift in economic alignment toward the EU, for the sake of both convenience and necessity. If this economic shift would lead to something more, it’s harder to say.

While there is much political debate revolving around whether Northern Irish business is better served by its EU or UK relationship, Gormely said ultimate ramifications of such conversations wouldn’t be seen for years.

“We’ve been at it for a hundred years, discussing it. So it will probably take another 25 before we have evidence on what is the best outcome,” he explained.

But Gormley is skeptical of those who think the business ties to the Republic and Europe will lead to weaker ties with the UK.

“People very seldom vote for revolution when they’re doing well. I think in Northern Ireland, if the protocol was implemented properly and created that prosperity, I do think it would change people’s desire to want to be a part of an all-Ireland,” Gormley said. “If the protocol is not implemented [correctly] and Northern Ireland becomes more and more disadvantaged, then I think you’ll see the point where people go, ‘Hey, maybe our interests are better served by focusing on Dublin and Brussels.’ It will take a long time to get there. But it’s that type of debate you’re seeing.”

People very seldom vote for revolution when they’re doing well. Richard Hogg, Precision Gear Company

Hogg agreed that he didn’t foresee business and politics overlapping. An economic shift, while perhaps certain, would not indicate a political one, though he joked many may try to connect the two.

“I’m always saying that within Northern Ireland, we can politicize anything. But not from a business point of view,” Hogg said. “We will trade with whoever. I think that we’re better staying within the UK, from a business point of view, at the moment. I think we’re stronger. But I’m also pro-Europe.”