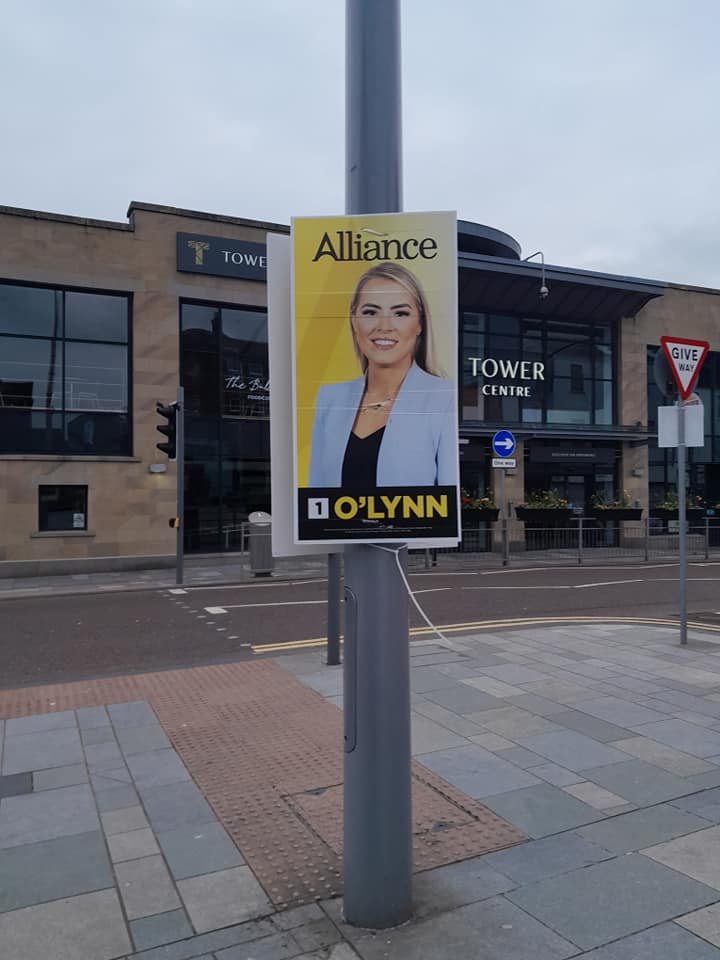

Patricia O’Lynn, a 32-year-old Alliance Party member of the legislative assembly, never intended to become involved in local politics.

She was 8 when the Good Friday Agreement ended the 30-year battle between groups like the Irish Republican Army that wanted to unify with Ireland and the British Army and groups that wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom. But O’Lynn was raised on a simple mantra – get educated, keep out of trouble, and get out of Northern Ireland.

While her sister sought higher education in England, O’Lynn stayed close to home, completing her doctorate at Queen’s University in Belfast. But she traveled to the U.S. every summer for various opportunities, including a 2016 internship with the late U.S. Sen. John McCain of Arizona.

In the last days of her D.C. internship McCain asked her what her plans were. She started to talk about a vacation plan with her sister when McCain stopped her and said she needed to start her own political career in Northern Ireland.

“When John McCain tells you to do something, you never disagree. You listen, so that’s what I did,” O’Lynn said.

She was running in an election within three months. This year, she became the first woman and the first member of the Alliance Party elected from the North Antrim region. She won by 288 votes.

She enters a Northern Irish Assembly largely divided between those who support unity with Ireland and those who want to maintain connections with the United Kingdom. Alliance doesn’t focus on these big, defining issues, but rather on healthcare, education and how to keep more young people from leaving.

O’Lynn has watched her peers leave Northern Ireland, and she knows stopping the so-called “brain drain” from the region will take tackling multiple issues.

“We see people born into families who bore the brunt of the Troubles feeling vicarious trauma, and all the social ills that come with poverty and poor mental health are exacerbated by division. COVID-19 isolation created a pressure cooker of issues with people suffering it even more,” O’Lynn said. “Young people want to live somewhere where they don’t have to have socialization couched by religious beliefs, or where they’re not going to be attacked for their sexual orientation or political views.”

The concerns of this new member of the Northern Irish Assembly echoed in a 2021 report by Belfast-based think tank Pivotal.

Pivotal reported in 2019 more than 17,000 students left Northern Ireland for education in other parts of Great Britain, while only 3,400 students came to Northern Ireland.

This exodus of students to other countries has hurt the region’s lagging productivity rates. UK’s Productivity Institute reported in 2021 that Northern Ireland is one of the worst-performing UK regions, with an output level 14% below the overall UK level.

In downtown Belfast, Cliodhna NicBhranair, a 28-year-old development officer at the republican James Connolly Visitor Centre, recalled her story of whether to leave or stay. She decided to stay and study Irish history in Belfast while her cousins went to England, followed by her aunt and uncle. She said the efforts to retain young people did little to help her as most government policies have focused on research-based careers that show more concrete benefits to the region’s economy and development.

“There are still opportunities here, but certainly there is underinvestment, especially in the arts sector,” NicBhranair said. “There is less long-term vision for investment outside of STEM fields that will encourage sustainable jobs in the gig economy, which can be hard for people like me trying to build a life here.”

But STEM investments continue to pay off. According to a recent report from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, the cybersecurity sector contributes £5.3 billion across the broader UK economy, a 33% increase from just two years ago.

NicBhranair noted that large portions of the systems to aid young people are not government-funded, but religious or nonprofit. She pointed to her language school and her job at the Connolly Centre as both examples of privately supported entities.

“I would not be here without giving to our community and their giving back. This is only sustainable from the help of local people outside of government assistance,” NicBhranair said. “The obvious answer, for me, to the lack of services and infrastructure and our social issues is to advocate for our own identity, to have a voice ourselves for our country. Young people are fed up and Westminster often doesn’t care about us, but we’re not economically viable on our own by any stretch.”

Chris Quinn, the director of the major non-partisan youth advocacy group Northern Ireland Youth Forum, has done his own research on brain drain and watched many of his group’s participants, who range from ages 11 to 25, go abroad after high school. Quinn sees the staggering rate of mental health issues, which is influenced by intergenerational trauma among families afflicted by the Troubles, as part of students’ desire to leave Northern Ireland.

According to the forum’s 2022 Manifesto for Change, more than 20% of youth in NI suffer “significant mental health problems” by the time they reach 18, and Northern Ireland has the highest suicide rates in the United Kingdom. Quinn said youth in Northern Ireland are underserved by mental health care in the country, stating wait times from general practitioner-referred cognitive behavioral therapists are typically 12 weeks long for only six sessions. The forum has set aside therapeutic suites in their office for their participants who cannot access timely mental health resources at school or through their doctors.

“Lots of young people see a better future away from here with our high cost of living, unstable government and massive employment issues. They go all over the world to get away from the uncertainty.” Chris Quinn, director of Northern Ireland Youth Forum

“Lots of young people see a better future away from here with our high cost of living, unstable government and massive employment issues. They go all over the world to get away from the uncertainty,” Quinn said. “You often have to go to England to receive services if you are acutely vulnerable when you really need people around you that love you instead of being shipped away, which is more traumatic. The Department of Education needs to be held accountable for turning a blind eye to it and focusing on GCSE’s, which just adds pressure to students.”

There is not one easy answer to addressing the many factors leading to brain drain in Northern Ireland, but Quinn said one avenue to compel students to stay outside of greater investment in local industries is addressing their top issues with material conditions in NI. According to Belfast-based research group LucidTalk’s spring 2022 poll, 56% of respondents aged 18-24 ranked rising costs of living as one of their top four issues, followed closely by 53% stating health service policies.

Emily Tschetter

Quinn said many of his participants have expressed frustration with Stormont’s dysfunction and exasperation with their Assembly reps’ lack of policy action after they’ve lobbied on their issues, which he sees as part of why students are seeking more progressive countries with clearer paths for getting their voices heard.

“There’s a massive tokenistic tendency to get young people into Stormont connections, check a box with their voice and send them off without acting,” Quinn said. “As it is at age 16, you can sleep with your MLA (Member of the Legislative Assembly), but you can’t vote for them. You can go to war and work, but you can’t vote, and it doesn’t make sense and makes young people feel disenfranchised. They just want to know they’re being heard.”

Without a clear plan in place in the Northern Ireland Assembly and Parliament’s Northern Ireland Affairs Committee’s recommendations on increasing opportunities for skilled workers still pending, the rate of students leaving remains high and research by think tanks like Pivotal show little sign of the brain drain stopping. Quinn and O’Lynn are both encouraged by seeing many younger candidates and women run in the 2022 election for MLA seats and hope more people see a place for themselves in making change in their home country, rather than leaving for good.

“We have major problems here for young people. The way politics is designed feels like it’s for the pale, male and stale of the world, but we’re seeing more and more parties putting forward diverse candidates,” Quinn said. “Having diverse voices in Stormont is the best way to make things work, so everybody has a voice and can advocate for the changes they need.”