The country’s first and only ketamine clinic offers a private alternative thanks to a father-son duo committed to making it work

HAMILTON, U.K.—Every morning, Sophia Vasconcelos walks the same 20-minute route through the streets of Hamilton, climbs three flights of concrete stairs, and rings the bell to an apartment door marked with a taped-on sign that reads “Eulas Clinics.” It’s been five months since she left Portugal to begin her internship at the first and only ketamine therapy clinic in Scotland.

“This job doesn’t stress me because I like what I’m studying and what I’m doing,” says Vasconcelos, who’s Brazilian and studying for her graduate degree in psychology at the Portuguese Catholic University in Porto. “During this internship I realized that I have so many ideas and perhaps I want to do a Ph.D. in aftercare or become a psychologist.”

Photo: Brooke Bickers

Vasconcelos came to Scotland with a personal connection to wanting to know more about using psychedelics to help people. She personally avoided substance abuse after watching her grandfather develop psychosis from chronic LSD use. But while she was attending university in 2021, she was in a car accident that left her in the hospital for a week, unable to walk. The accident triggered anxiety and post traumatic stress disorder that only subsided after she traveled to the Netherlands to take psilocybin for the first time. That moment changed everything.

“I realized that, OK, if this helped me, and I had no knowledge of how it works, imagine if I study more how I am going to be able to help people who suffer with mental illness,” Vasconcelos said.

Vasconcelos spent the last summer looking for clinics all over Europe and around the world that would be willing to work with her during a required supervised internship for her program. She then stumbled on the small, fledgling Eulas clinics, applied for a position and got the green light.

Now, she’s observing patients, filing reports, taking care of patients and managing the social media platforms for the clinic. But it’s still not smooth sailing for her or anyone working here because of strict government monitoring and regulations.

“It feels like we’re taking one step forward and taking two steps back,” Vasconcelos said. “It’s so frustrating.”

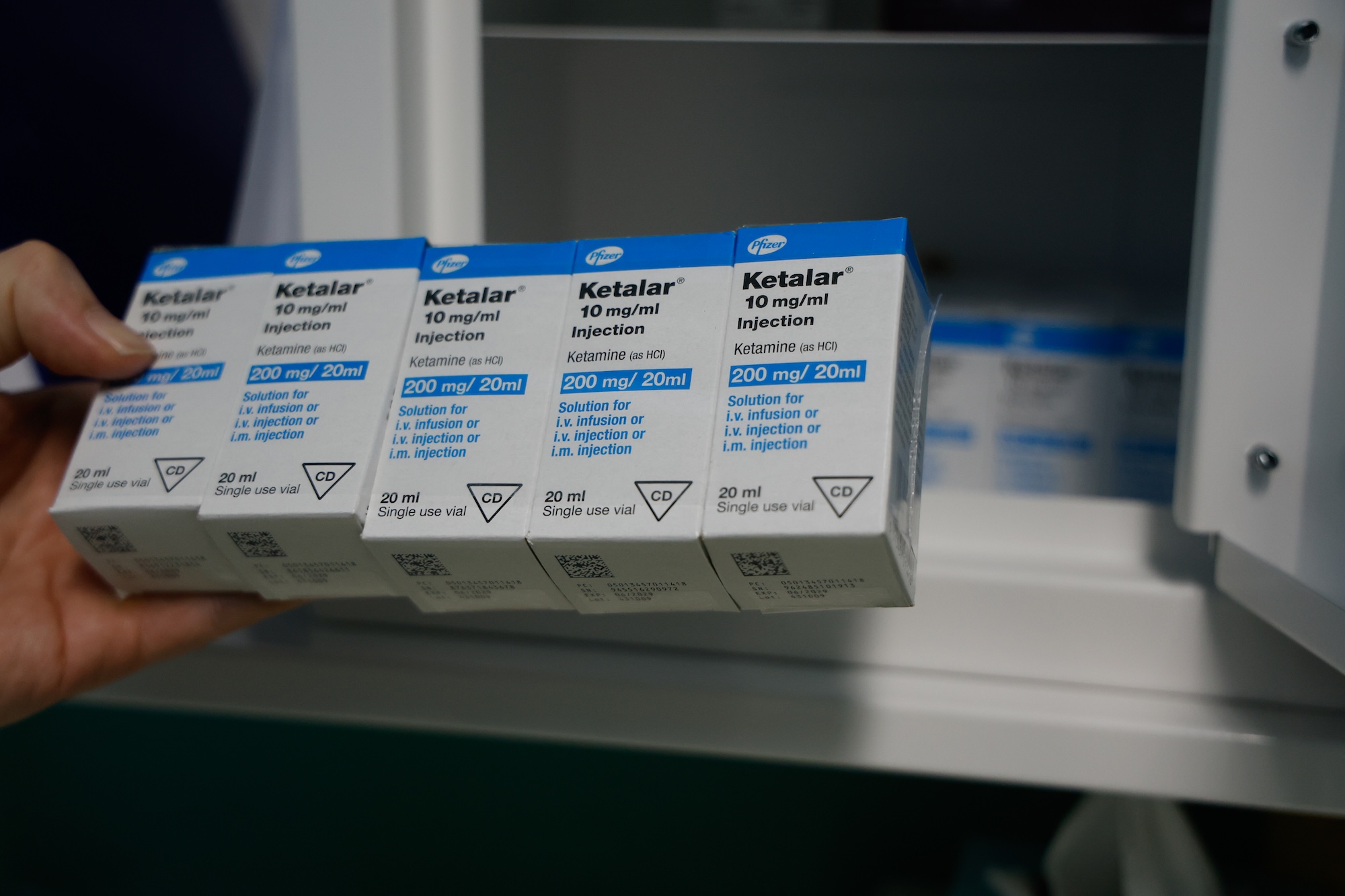

In other parts of the world, clinics and researchers are embracing ketamine-assisted therapy for its rapid effects on various mental diagnoses, including severe depression, post traumatic stress disorder, and on dependency to some drugs such as alcohol and heroin. The United States has more than 700 for-profit clinics offering sanctioned ketamine therapy. But in Scotland and the U.K. as a whole, adoption has been slower. While supported by scientific research, ketamine treatment continues to face battles against long-standing stigma and public fears rooted in its recreational use and abuse — which is considerable.

Currently, ketamine is a controlled Class B drug in the United Kingdom, along with cannabis and amphetamines, but because of illegal use reaching record levels in 2023, the government is considering classifying it as a Class A drug. That will mean greater penalties for possession and distribution and tougher battles to keep the clinic open.

Getting Their Start

The Eulas Clinics father-son founders, John and Sean Gillen, both say they put their life’s savings into this place, beginning with its founding in 2024.

John Gillen was a racehorse jockey and trainer well known in Scotland who achieved the status of “head lad,” or manager of a racing stable, when he was in his early 20s. He then went on to be a trainer with horses that won and placed in prestigious races.

But he also struggled with alcoholism, and he was open about it with his family. Sean, who runs the clinic now that his dad is retired, talked about John going to AA meetings and hospital detoxes while he was growing up. But the thing that eventually healed him was the library.

Sean gave a small laugh under his breath when he recalled his father spending hours in the library reading about psychology, addiction and spirituality instead of going to meetings.

“I think he realized he should feel safe and stress-free all the time and the same feelings happened in the library,” Sean said. “That’s how he got well from his addiction.”

It was through the ups and downs of recovery and lots of time hitting the books that the Gillen family found a place in the mental health field. Together, the pair racked up 40 years of experience working in rehabilitation centers. John initially founded a rehab called Abbycare with his friend John McLean in 2003, but decided to step away to open a day center for addiction in 2006. By 2011, John started a non-medical rehab, which operated until its closure in 2012. Nine years later, he found a new calling with the launch of Nova Recovery Team in Largs.

Sean joined his father at Nova the year it opened, bringing with him over a decade of experience from working in rehab centers across Scotland, including Abbycare. Throughout his career, he moved between positions at his father’s facilities and other rehabilitation centers, steadily progressing from a drum teacher to a support worker and, finally, into more managerial positions.

While working together at Nova, a staff member discussing psychedelic therapy and research caught their attention. Together, they decided to approach the company directors with the idea to use psychedelic medicine to help their clients.

“We saw places like Russia were using ketamine for alcoholism and they were using LSD for mental health,” Gillen said.

But the directors said no because they viewed it as too big of a risk to take. “And I just knew my dad and I would end up starting this ourselves,” Sean said.

Over time, they found this small set of rooms to rent in the former office of an architect. It’s in an apartment complex in John Gillen’s hometown, about 14 miles from Glasgow, Scotland’s biggest city. But it would be two years of paperwork, prep and patience before that space opened as one of only a handful of ketamine therapy clinics in the U.K., mostly based in London.

Facing Hurdles

Eulas Clinics and its like continue to face pushback in the U.K. because of ketamine’s reputation as a mind-altering party drug and as a horse tranquilizer.

Nightlife has become closely tied to ketamine use with multiple studies showing that people who go to nightclubs and pubs more often are more likely to use ketamine. It’s primarily popular with teens.

An annual report from the Scottish government, “National Mission on Drugs,” found that for 2022-23, ketamine was the third most popular drug favored by teens, after cannabis and cocaine. Of those students who answered yes to a question about ever having taken illegal drugs, 36% said they’d tried ketamine.

This steady increase in ketamine abuse worries Anne Marie Ward, CEO for Faces and Voices of Recovery, an addiction recovery charity. After overcoming a decade-long struggle with alcohol and drug use, Ward founded the charity in 2013 to advocate for the rights of recovering and active addicts. It lists 5,000 members U.K.-wide and mainly serves to advocate for more treatment options and access for people seeking help with their addictions.

Ward found herself working with those battling ketamine abuse intermittently throughout her career and took it upon herself to become a powerful voice in bringing attention to its increasing use. “While ketamine use hasn’t yet overtaken opioids, benzos or cocaine in the cases we see day-to-day, we are receiving a noticeable rise in concerns from families, communities and front-line services,” Ward wrote in a text.

The drug landscape of Scotland could be explained as a period of significant transition. From 2009 to 2018, there was a 33% increase in Scottish citizens aged 16-54 claiming they had used ketamine. Cocaine and MDMA are still heavily used, but recreational and club users are turning to drugs like ketamine because of its cheap cost, its availability, and the wrongful perception that it is a safer drug to use. But this side of ketamine use is not always accurately displayed.

In Public Health Scotland’s Drug-Related Hospital Statistics for 2023-24, the report does not break down ketamine use into a separate category. Instead, it often gets included under the “multiple/other” drug category, since it’s often taken with other substances, such as alcohol and ecstasy.

Most users aren’t reporting ketamine addictions. And a lot of them are teens. “The lack of visibility is a problem in itself,” Ward said. “We can’t fix what we don’t measure properly, and Scotland desperately needs better real-time data on emerging drug trends like ketamine.”

Side Effects and Need

Under the harsh light of surgeon Mohammed Belal’s headlamp, he’s seen just about any conceivable abnormality of the bladder. As a highly specialized reconstructive urologist based in Birmingham, England, he thought he’d seen it all. But he had never encountered K-bladder until 2006 when a patient complained of having terrible pain when trying to urinate.

“I remember the time because he goes, ‘Oh, I take a lot of ketamine,’ and I was like, yeah whatever,” Belal said. “But then we looked inside and saw these inflammatory masses within the bladder and thought the guy had cancer.”

Belal’s 2006 case would be the start of him treating what’s come to be called K-bladder, which develops when regular ketamine use scars and damages the bladder, causing it to shrink.

He saw cases surge in the last five years, “I’d say about 2019 and during COVID,” Belal said. “The second surge, we were really not on top of because the number of patients turning up with ketamine abuse has dramatically increased, sadly.”

U.K. government statistics show that during the pandemic, roughly 1 in 125 people were misusing ketamine, resulting in a roughly 1% increase from the previous year.

While ketamine use was surging, general substance use deaths were going up, too. In 2023, there were 1,172 drug misuse deaths registered in Scotland, an increase of 12% compared with 2022.

Simultaneously, the need for mental health services during and after the pandemic also jumped. The global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25%, with an estimate of 53.2 million new cases of major depressive disorder and 76.2 million new cases of anxiety disorders arising worldwide.

In June 2024, Public Health Scotland revealed 29,982 Scottish citizens of all ages were referred for psychological therapies, an increase of more than 8,000 from June 2021.

The Gillens wanted to step into that need for treatment.

They knew they had their work cut out for them in convincing the Scottish government. Although ketamine is approved in other countries as a drug that can treat addictions to other drugs like alcohol and heroin, the Gillens were familiar with reactions and problems in Scotland when it comes to methadone as a means to treat heroin addicts. While knowing ketamine is in another class all together, they knew it’d be an easier sell to put forward ketamine as a treatment for severe depression. That’s the argument they made and backed up with research and it’s what won them approval to open Eulas Clinics.

What Treatment Looks Like

Photo: Brooke Bickers

To start treatment at Eulas Clinics, clients must complete a pre-assessment meeting with a psychiatric staff member to monitor how risky the therapy would be for the patient. Once approved, they begin a six-week treatment plan and undergo 12 psychotherapy sessions. Four of these sessions involve IV doses of ketamine. The main goal of this process is to permanently change the brain’s function and offer a path to healing that traditional treatments may take months to achieve, said Sean Gillen in an interview at the clinic.

He claims 75% of their patients have experienced significant improvement after just one infusion. The remaining 25% saw improvement after the fourth infusion. But those numbers are low. Since opening last year, the clinic has only treated 12 patients, the majority of whom live outside of Scotland. In a country where healthcare and even prescriptions are essentially free for residents, it can be difficult for citizens to afford the £6,000 Eulas Clinics charges for treatment.

The price never mattered for Laura Bowles. Originally from Scotland, Bowles now lives in France as a journalist. She finished her last session at Eulas Clinics in January.

“For the first time in 20 years, I have control over my anxious thoughts and feelings,” she said over email.

Bowles said she and her husband had been tracking research about psychedelic treatments for her dual diagnosis of anxiety and treatment-resistant depression for years. Bowles decided to take a chance with Eulas after being denied treatment in Switzerland as a nonresident.

Before that, Bowles visited multiple psychologists, tried hypnotherapy and took medications. None of them solved the real problem, she said. After meeting with the Eulas staff over a Zoom call, Bowles was convinced.

“Eulas was a completely unique experience,” Bowles said. “It allowed me to focus exactly on what I needed to, to heal.”

Almost four months after completing treatment, Bowles said she’d finally found relief from her anxiety.

Sean Gillen says that’s been a common experience with his clients.

“No one has ever asked to come back for more,” Sean said. “They can if they want to, they can give us a phone call and we’ll do it. But no one has asked.”

Despite these successes, Sean says that Healthcare Improvement Scotland has made it difficult for his clinic to truly take off.

More Red Tape

From the first time an inspector from Healthcare Improvement Scotland checked on the clinic six months after its opening in December 2024, Sean’s take was that it was clear the government had already been rubbed the wrong way about his business. The inspector looked at patient paperwork, staff files, medicine audits, health and safety paperwork and the general safety of the building and never found anything wrong with the clinic, he said. HIS typically inspects and regulates private medical practices, and is usually well-versed in handling a range of health and social care services.

Photo: Brooke Bickers

“Because we are the first people doing this, they weren’t exactly sure how to regulate it,” Sean said. “And since we’re doing something that’s unusual to them, they deem it high risk.”

A white three-ring binder with the word “Policy” in bold letters sits behind Gillen’s desk. It contains the various regulations and changes to those regulations governing the clinic.

“The person who wrote those policies has done it 30 times,” Gillen said. “We’ve been scrutinized much more than anybody else in this country.”

Ann Ross, an academic and researcher with the University of Edinburgh, was a pre-evaluator for the research foundation, Wellcome Trust, to study the feasibility of ketamine in medical practices like Eulas. She later worked closely with the clinic as it was being approved for operation.

Since psychedelic-assisted treatment is increasing globally and within the U.K., Ross created the Scottish Psychedelic Research Group at the university. Along with research, her group also contributes advocacy.

“It’s my belief that actually the law has created more dangerous drugs,” Ross said, referring to ways people combine drugs to self-medicate.“From my understanding, the law can take several decades to catch up.”

Sean had became a member of her group in 2023 with the goal of pushing research to prove that drugs like ketamine are capable of being much more than a pill popped in a club or an anesthetic for horses.

He’s expressed how his frustrations stem from the fact that he still has to turn patients away who have other disorders that aren’t related to treatment-resistant depression while other countries, including the U.S., have multiple ketamine clinics that can operate without such limitations.

Making It Work Here

For now, approved clients are figuring out how to make the trek to Hamilton work. Once they find the out-of-the-way clinic, they’re greeted by Sean, Vasconcelos and the rest of the clinic’s team, consisting of a manager, two psychiatrists, two licensed therapists, a pharmacist and an anesthesiologist.

Photo by: Brooke Bickers

The space is small but cozy with about four rooms, including Sean’s office and a lounge taking up the most space. As a medical office, the Gillens had to install industrial sinks, glossy floors, and wall-hung heart monitors. But this is also a therapeutic space, so they’re trying to accomplish that feel on a tight budget.

In the infusion room, no overhead lights are turned on. The blinds are always drawn and the only light source comes from two potted trees strung with Christmas lights.

“The space is very important.” Gillen said. “People need to feel relaxed and also kind of special.”

Across the hall, the walls are still a stark white instead of the deep green Gillen chose to paint the waiting and infusion rooms. Those white walls are a reminder to Gillen that there’s still a lot he wants to accomplish when it comes to improving the clinic.

But with no extra help from outside funding, like those clinics run by the NHS, more improvements will have to wait for more clients to find and commit to Eulas Clinics.

He’s not giving up.

“We want to form partnerships with the NHS and other organizations to treat more conditions,” says Sean. “This is really good results here, and it’s a lot cheaper for someone to come here than to go to rehab.”

This story is part of a healthcare series produced by the International Reporting program at the University of Montana School of Journalism. Read more from this Scotland-based project, as well as reports from other countries, at Montana Journalism Abroad.