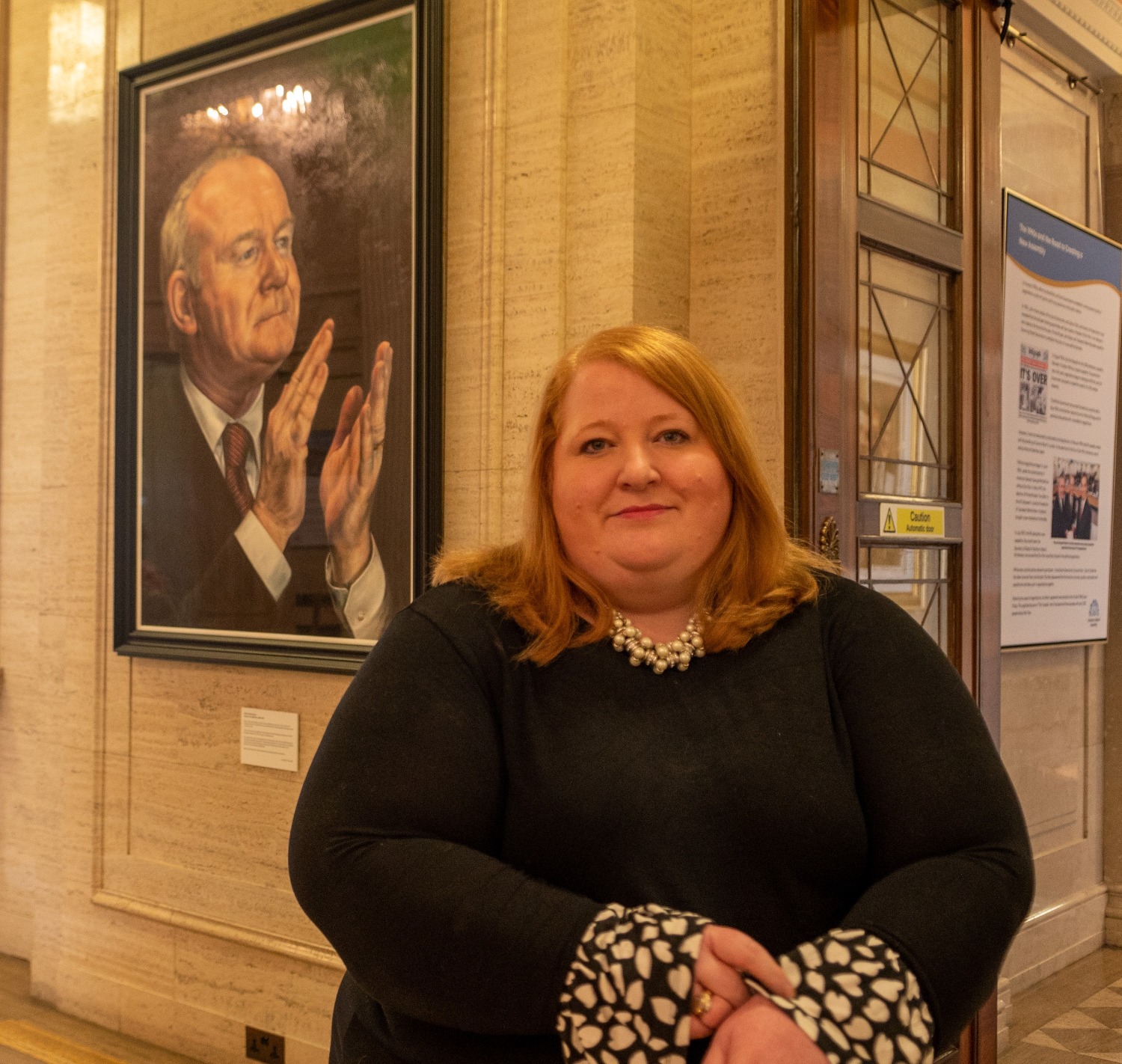

In the Great Hall of the parliament buildings at Stormont, Naomi Long poses for a photo between portraits of two famous Northern Irishmen.

Andy Mepham

There’s Martin McGuinness, former nationalist deputy First Minister, and Ian Paisley, former unionist First Minister. They’re easily recognizable and huge on the walls of Northern Ireland’s legislative building. For many, the two represent the bitter divide that’s existed between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists. Even after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement — meant to bring an end to the decades of sectarian violence known as the Troubles — divisions still permeate many aspects of Northern Irish life, especially politics.

Andy Mepham

Now, their images bracket Long, a powerful woman, as she strategizes how to move beyond NI’s old political and cultural divisions.

Long is the head of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, the country’s most prominent “cross-community” group, which recently came off a wave of success in the Northern Irish Assembly’s May 5 election. With 13.5% of the vote, her group leapfrogged over both the pro-UK Ulster Unionist Party and the pro-Irish nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party to become the third-largest political faction in the regional legislature.

Many are hesitant to label the group’s wins as proof voters are trending away from nationalism and unionism. Still, Alliance’s success has caused some experts to question if politics are, indeed, changing in Northern Ireland.

Fueled by public frustration over border issues raised by Brexit, and powered by a rank-choice voting system that allows second- and third-choice parties to emerge with seats, the Alliance Party appears to be systematically chipping away at a political system so structured around the unionist/nationalist divide that a candidate must choose one side or the other or be relegated to the status of “Other.”

Post-conflict politics

“[T]he Good Friday Agreement has worked, and it has provided the kind of lack of violence that has allowed people to live freer lives … and has given people a taste of a different kind of Northern Ireland,” Long said in a recent interview. “People are embracing that diversity in a way that would have been difficult to do during the Troubles. And I think what we’re seeing now in elections is that starting to be reflected in the electoral outcomes.”

In many ways, Brexit re-fortified the old unionist/nationalist divides. Identity suddenly became a policy issue as well as a cultural one, when voters were asked if they’d rather stay with the European Union and Ireland or align with the other parts of the United Kingdom and leave.

Northern Irish voters voiced their desire to stay. But they lost out as a majority in the United Kingdom voted to leave the EU, launching the region into years of Brexit limbo.

But in this period, among turbulent policy changes and the Irish border’s tug-of-war debate, a transition away from the political extremes began to bubble in Northern Ireland. It’s one that perhaps started before, as NI continued inching toward a more progressive generation of voting-aged citizens.

In what’s been labeled as the “Alliance surge,” or the rise of the “Others.” Alliance has learned how to play the Northern Irish electoral game and has carved out a unique spot.

“This is new. The growth of the middle ground — how people in Northern Ireland are thinking differently about their future,” said Sarah Creighton, lawyer, writer and political commentator from Northern Ireland.

“My parents, when the bombs were going off, it was completely different. The absence of that really has changed people’s views on things. They’re able to think about issues in a very rational way” Sarah Creighton, political commentator

In the May elections, Alliance won 17 seats in the region’s 90-seat legislature, more than doubling its previous best. In fact, Alliance was the only party to gain seats compared to the last election in 2017.

Northern Irish elections are complicated. Who wins a seat is oftentimes the result of a mix of coalitions, luck and timing. Rank-choice voting means those who win seats aren’t always the most popular candidate, but often, also, the second- or third-choice candidates.

First-preference votes indicate the party constituents are primarily backing. And Alliance saw a significant jump in those voters, but also strong second- or third-preference votes from both sides of the political divide. Those seats demonstrate a keen strategy that has been working for the party: Build up confidence in your group to win seats, and get first-preference votes from a growing base of Northern Irish voters fed up with the unionist/nationalist divide. But also: Remain acceptable as voters’ second or third choice by mainly staying quiet on the most divisive issues.

“I think, first of all, [the first-preference increase] reflects the fact that more and more people in Northern Ireland no longer define themselves primarily as unionist or nationalist,” Long said.

Alliance capitalized on constituencies where it had strong first-preference backing in 2017, running another candidate in those regions this year to try doubling its seats. Each constituency elects five members to the parliament, and piggybacking on areas where Alliance has done well allowed it to elect second candidates from the same locales.

But another part of the party’s success lies in its ability to squeak out seats — sometimes by only a handful of votes — in the so-called transfer. Northern Ireland’s rank-choice voting means a voter can select candidates as a second or third choice if they’re not sure their first-choice candidates will receive sufficient votes. If a voter’s first candidate is knocked off, their votes go down the list to the following prospect. The same happens if the first candidate from one party is easily elected, their “extra” votes go to second choices.

Long said she thought Alliance’s message, one of reconciliation instead of division, that avoids unionist or nationalist labels, is inherently a more “transfer-friendly” one.

“That’s a message that is going to attract people who, you know, may have unionist or nationalist aspirations, but as a second or third choice to their own party will say, ‘Well, yes, [Alliance candidates] are people we could also trust to articulate on our behalf,’” Long explained.

Being transfer-friendly is a big part of Alliance’s strategy, said Clare Rice, a research associate at the University of Liverpool. It helped seal the deal on many of the seats the party won in this election.

“I would bet, no doubt, that the party is known for number crunchers and people really deeply engaged in mathematics and politics.” Clare Rice, University of Liverpool

“I would bet, no doubt, that the party is known for number crunchers,” Rice said, “and people really deeply engaged in mathematics and politics.”

But that threading of the needle between pro-Irish and pro-British may not last forever. Some experts, Rice said, believe the party’s success is a sustainable strategy, while others are not sure.

“There are different perspectives circulating with regard to what the election results mean,” Rice said. “It’s very difficult to say, actually, is this a confident change in how people are thinking about politics and how they’re voting at the assembly level? Or is it something that is tentative, and that might be overtaken by a hardening of the extremes of the political spectrum?”

Andy Mepham

The extremes of the political spectrum certainly still exist in Northern Ireland. In late May of this year, thousands marched in the Orange Order parade marking NI’s centennial. The parade, delayed a year due to COVID, was a celebration of everything unionist and focused on the region’s connection to the United Kingdom and the crown.

“We have no intention of becoming part of an all-Ireland. Save your breath,” Rev. Mervyn Gibson said to cheers of thousands of Orangemen and unionists.

As unionists and nationalists grapple over the Irish border, with different takes on a United Ireland or a hard boundary between the two countries, Alliance has benefited by not taking a clear stance on that disputed stretch of land.

“I guess [Alliance’s border stance] is an easy one to pick up those votes. And it’s also an opportunity to pick up unionists, and there’s an opportunity to pick up nationalists,” said Sophie Whiting, a University of Bath lecturer studying UK political parties. “Like, pragmatically, why would the party necessarily take a stance on [the border] now?”

And pragmatic voters, from both sides of the aisle, are picking up the message, said Peter McLoughlin, a lecturer in politics at Queen’s University in Belfast.

“[Alliance] seem to be winning a lot of my students,” McLoughlin said. “Liberal, more educated, younger unionists — and nationalists.”

Much of Alliance’s message, McLoughlin said, attracts these demographics, who may still identify as unionist or nationalist, but want “pragmatic and sensible” representation at Stormont.

Alliance has also benefited from unionism’s fragmentation and was, in fact, born of some of that splintering. It grew out of the New Ulster Movement, a push in the late 1960s to promote moderate and nonsectarian policies. It has tended to sidestep the constitutional question of the border that became so controversial during Brexit.

Alliance focuses on the bread-and-butter issues of Northern Irish politics, McLoughlin said. The group takes liberal stances on health care, education, women’s rights, while avoiding the more polarizing question of a border poll.

“So, if you’re a liberal, the Alliance Party kind of ticks a lot of boxes,” said McLoughlin. “It’s really kind of parking the constitutional question. It’s saying, ‘Well, you know, maybe if things were massively different in the future, we might engage that debate, but right now, let’s focus on rights for everybody in Northern Ireland.’”

But, is that success sustainable? As the third-largest party in the legislature, analysts are wondering how long the party can go without speaking out on the border in one way or another. As McLoughlin said, it will become an issue someday, whether Alliance takes a stronger position or not. And NI’s political system is built around the answer to that question, historically favoring those who take strong positions on these divisive issues.

For the group to really have power in Northern Ireland’s power-sharing agreement, it would need to achieve one of two things. First, it could win the most seats in the assembly and elect an Alliance member to First Minister.

The second-in-command, the deputy First Minister post, is reliant entirely on the size of the designated groups, Rice explained. It’s not as simple as winning the second most seats. For Alliance to have the chance to elect a deputy, the “Other” designation would have to beat out unionism or nationalism for number two. Since Alliance dominates the “Other” designation — wiping the Green Party off the map this election and leaving People Before Profit with only one seat — it is essentially a coalition of one.

And, the question remains if voters would get Alliance to the point of first or deputy first minister on bread-and-butter issues alone.

“That’s really hard to call,” McLoughlin said. “We still have real, profound divisions and Alliance — it’s kind of a chicken and egg thing there. Unless you have a real, powerful position, you can’t transform society.”

But Rice from University of Liverpool said the Alliance track may work for a while yet.

“Alliance is in a bit of a sweet spot in Northern Irish politics, in terms of being able to capitalize on frustrations at the stop/start institutional situation… while still being seen as a pragmatic — sometimes alternative to unionism and nationalism, and sometimes just a home for people who maybe feel a bit of both,” Rice said.

Long is still running the numbers.

“I have targets for the next elections, that are not just about holding what we have, but actually about further growth.”