Despite the cold rain blanketing Belfast, a small group gathers outside the gates of the baroque City Hall. Rain is common enough and doesn’t stop much here, including tourism.

Asa Thomas Metcalfe

Paul Donnelly smiles through an introduction and offers a joke. He’ll have one to match about the place of origin for each person who joins.

Donnelly is a Belfast native who spent years working in conflict resolution and mediation. In 2013, he and his associate, Mark Wylie, started Dead Centre Tours, leading guided walks that explore the culture and history of his Northern Irish city. It’s a history with mainly two sides: Catholic or Protestant, Republican or Unionist. The tour operators’ gimmick is in the name: They’re right there in the center, without swaying decidedly either way. It’s a rare offer here.

Some would say that history of violence, especially the era known here and elsewhere as the Troubles, is still too fresh and best left off the tourism menu, that inviting outsiders to view the pain and misery is ghoulish. But Dead Centre and a handful of others have championed an effort to tell it in a way that is true to the damage done and fair to those affected, while not celebrating the actions of the perpetrators. That’s not easy, says Donnelly.

“There was no six degrees of separation,” Donnelly said. “We all experienced it.”

From the late 1960s until a peace accord in 1998, Northern Ireland was mired in the Troubles. Republican groups, led by the Irish Republican Army, battled British and Northern Irish forces that aimed to keep the region under the control of the United Kingdom.

Although the violence has largely ended, the identity politics at the root of it are still not fully resolved.

“I think in the context of Belfast, a solid narrative is almost impossible,” said Eimear Henry, Strategic Lead for the upcoming Belfast Stories Project. “I think it would be really difficult to capture the complexity of the city’s past.”

The Belfast Stories Project, led by the city council, is an exhibition collecting a variety of voices from across the city to craft a more inclusive version of what Belfast is and who lives here.

“A lot of the market research indicates that there’s still relatively low levels of awareness as to what Belfast’s story really is.” Eimear Henry, Strategic Lead, Belfast Stories Project

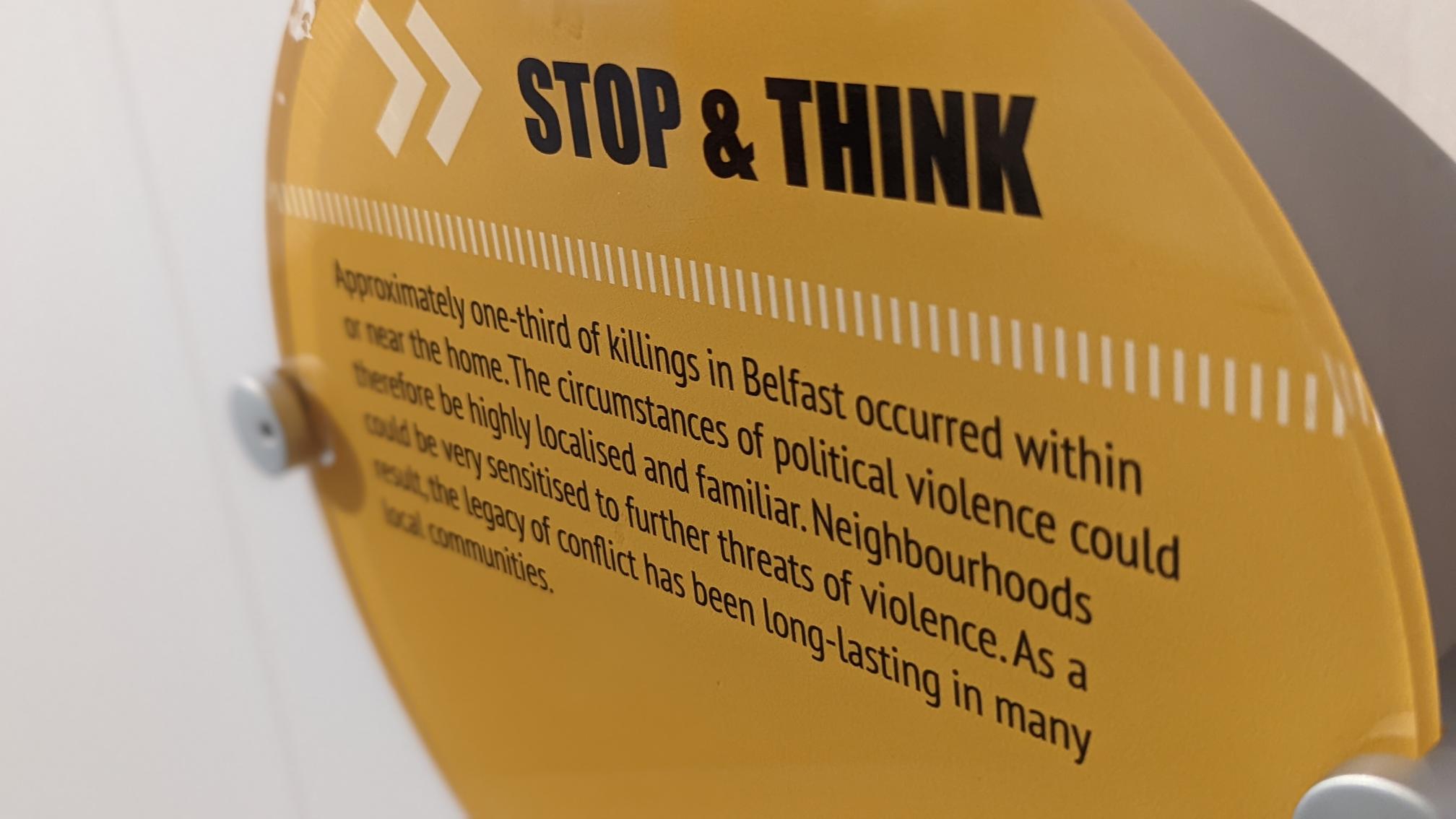

The Troubles devastated his small country and city. More than 3,500 people were killed. Before the peace agreement in 1998, whole neighborhoods were bombed out.

Roughly 52% of those killed were civilians not involved with any paramilitary group. They were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

By and large, the story of the Troubles wasn’t told by official entities. During and just after the conflict, many tour operators focused on telling their version, the ones they grew up with and their families and friends experienced, emphasizing the cruelty of the other side and acts of martyrdom by those they supported.

Guiding tours became a common source of employment for recently imprisoned fighters. Since they had been closest to the violence, they seemed the best prepared to discuss it.

“They’re not tour guides, and they’re not historians,” said Mark Wylie, co-founder of Dead Centre Tours. “It wasn’t necessarily better than historical fact or truth, but it’s just a perception. We call it the misery Olympics.”

In the early 2000s, an industry quickly grew from sectarian perspectives, and the official, government-run tourism boards were afraid to associate with either one.

“They never wanted to champion or promote conflict tourism, because it’s an incredibly contentious subject,” Wylie said.

Academics who study tourism and its effects on cultures refer to Northern Ireland’s conflict-focused brand as “dark tourism.”

Dark tourism has many levels. Some forms include the sites of mass murders, or museums dedicated to serial killers, but most dark tourism is based around battle sites like Gettysburg in the U.S. or the somber memorials of locations like Aushwitz in Poland.

In Belfast, the dark tourism focuses on the vivid painted murals that present members of either side in a reverent light or explicitly blame the other side.

The problem is visitors who aren’t aware of the political nature of the conflict or well-versed in its history can come away with a one-sided version of events. That goes on to be their understanding of Northern Irish history and culture.

“People who go on Troubles tours don’t actually realize that that puts them in a box that says they’re a dark tourist,” Wylie said. “They think they’re just doing a tourist activity of something that interests them, whether it’s unfolding death or not.”

Without changing this story, experts say, Northern Ireland fails to take advantage of the power tourism gives a place to shape the story about itself.

“Tourism allows for a group of people to display who they think they are for others,” said Eric Zuelow, a professor of European History at the University of New England in Maine.

“What do we want people to see? And what do we not want them to see?’”

He suggested that through the culture’s interaction with tourists, a community can find a sense of how that culture really views itself.

“At the same time that tourists are engaging with those people, they are thinking about who they are themselves and what makes them different from the people they’re seeing. Also, what is it about these people that makes them who they are?”

Tourists are fed a diet of information about the place they visit and whether they consciously understand it or not, it develops their understanding of the people who live there.

In Northern Ireland, tourism that seeks to appease one side of the conflict or the other doesn’t leave much opportunity to show the full perspective.

Another option is to leave out more recent violence by focusing on older histories.

“In Belfast City Hall they have an exhibition on the history of the city, and it goes into great detail from the formation of Belfast all the way through the 1960s and then just stops,” Wylie said. “You’ve got a room for reflection and a few quotes, but it doesn’t talk about the Troubles in Belfast at all because there’s no agreement on how to tell that story.”

But Wylie and others are trying to make sure that the history of Northern Ireland is accurately captured to explain what happened and the human toll.

“Our cultural expression has been shaped by the Troubles. Look at the role of music, for example, and how our music story also tells a story of conflict, but look at it through a cultural lens rather than a political lens,” Henry said.

The story of Belfast is just as much about peace as it is about violence and by looking at the atrocities of the past, looking through the peace walls and the murals, you can find a story of resilience and reconciliation.

“Some people say you have to leave the past behind,” said Donnelly. “Some people say you can’t move ahead until you’ve dealt with the whole past. There is no wrong answer.”