At the end of another long day of tending pregnant ewes, Alastair Armstrong kicked off his boots and fell into his bed. He was eight weeks into the sleepless nights of lambing season, but he had one more thing to do: he whipped out his phone and logged into Facebook.

Armstrong scrolled through story after story about restrictions imposed by the Northern Ireland Protocol, a result of a negotiated deal to allow the UK to leave the European Union without creating a hard land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Like many farmers in Northern Ireland, Armstrong runs a small, family-owned operation of 250 pedigree ewes. The demand for livestock like his exceeds local supermarkets, however, with his best customers purchasing internationally. In years prior, Armstrong loaded livestock onto lories to buyers in Austria, Germany, Switzerland and the UK.

But Brexit has changed all that.

For centuries the rural economy of Northern Ireland looked east. Since January 1, however, that model for NI farmers is often no longer viable.

While a last-minute trade deal averted tariffs and fees for now, the UK’s departure from the EU’s free trade zone has meant more paperwork and unprecedented delays for Northern Irish farmers and ranchers.

Under the final Brexit deals, Great Britain is now seen as a third country when bringing livestock into NI. That means Northern Irish farmers have to adhere to the health and safety standards of the Union, while still being controlled politically by the UK. While many experienced immediate shortfalls, NI’s agriculture workers, a sector of 49,000 mostly small-scale farmers, are anticipating changes in their business, markets and governing policies as the region navigates Brexit.

Beyond selling to markets in the EU and UK, farmers in Northern Ireland found suppliers across the Irish Sea. Pedigree farmers like Armstrong source breeding stock from Scotland to increase genetic diversity in their flocks on the small island nation. Annual trade like this is essential to Northern Ireland’s proud pedigree standard that helps drive a $400 million USD agriculture industry.

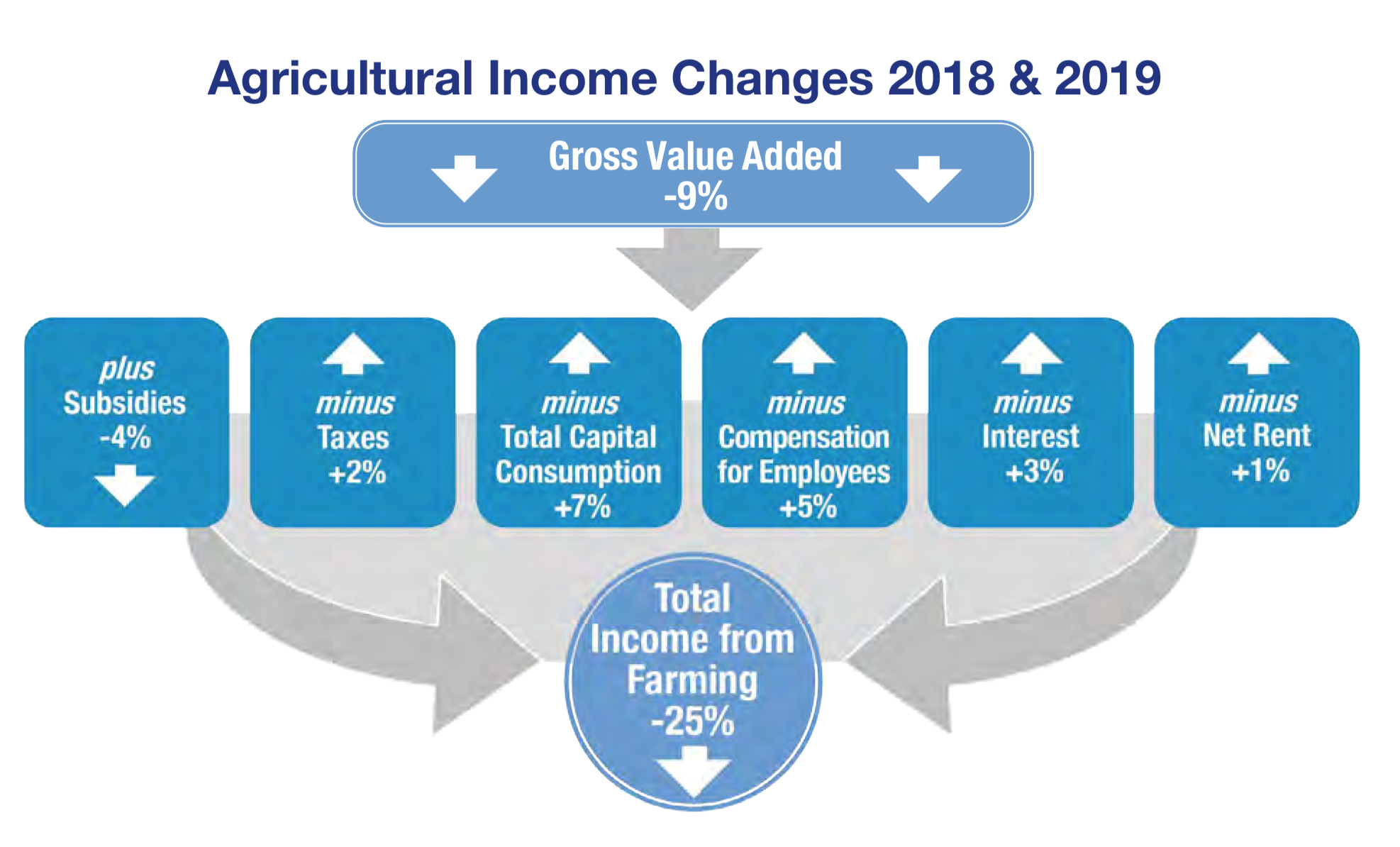

Soure: DAERA

In fall 2020, roughly 9,000 ewes and lambs were purchased by NI farmers in the Scottish lowlands, a sale totaling close to $2 million USD. These sheep would typically reach ports in Belfast and Larne in March, after coming of age to export and undergoing veterinary inspections. But because of Brexit restrictions, the wait has been longer than expected. Breeding sheep or goats are now required to take residency in GB for six months before being traded, where they’ll be met with a 40-day holding period to quarantine.

New requirements have forced NI farmers to pay steep livestock insurance rates on these sheep, while Scottish suppliers look for new, cheaper buyers on the mainland. Armstrong and other prospective buyers question the practicality of these rules, as lambing season comes and goes with few new breeding sheep reaching NI.

This is especially concerning when Armstrong considers paying to test prospective livestock for diseases like Scrapie, when their arrival date is uncertain. Armstrong said it costs up to $170 USD to bring a ewe in from Scotland, and he’s worried the chances his sheep could die in quarantine while paying to insure them outweigh the possible income.

“There is no point in us spending ‘X’ amount of pounds on an animal that then will not be able to come in,” Armstrong said. “We will have to pay that money and if [the animal] doesn’t qualify we will have to forget about it.”

Roughly 49% of all agri-food exports from NI were shipped across the Irish Sea to Great Britain, according to a 2017 Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) report. Under Brexit rules, farmers can bring livestock into Great Britain, but to return the animals will have to quarantine for at least 30 days, a stay many ranchers can’t afford. When farmers try to bring livestock back into the EU they must supply veterinary inspections and new identification to avoid animals entering the market that do not meet standards. However, the risk of not being able to bring their best animals home has caused many ranchers to pull out of the shows instead of risking delays that could result in the animal needing to be sold or slaughtered in Britain.

Credit: Eric Jones

Additionally, the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs in NI required farmers importing breeding stock, like rams and boars, to obtain a license for each animal shipment. James McCluggage, policy manager for the Ulster Farmers Union, said it’s something his members “can’t wrap their heads around.”

“Every day is bringing out something new of what is involved in the NI Protocol, an obstacle or a new problem,” McCluggage said, whose group represents 11,500 farmers and ranchers.

McCluggage said markets in Great Britain were the “front shop windows” for many ranchers looking to sell their product abroad. But major auctions in NI have been cancelled, too. The Balmoral Show in Belfast, which brought in 120,000 attendees and farmers was cancelled due to existing lockdowns in the UK. Social media and local markets have provided new opportunities for farmers like Armstrong, but the loss of such auctions have been felt.

“Brexit was going to be hard enough and then COVID entered the mix.” Alastair Armstrong, rancher

“Brexit was going to be hard enough,” Armstrong said. “And then COVID entered the mix.”

Originally, agricultural groups worried about inspections in the Northern Ireland Protocol trade agreement that caused delays for suppliers of perishable foods, like chilled meats, fruits and vegetables. Customers at large supermarket chains in NI saw empty shelves from backlogged goods within the first weeks of the new arrangement. But this is also the case for many goods vital to the agriculture industry. Armstrong also works for a livestock supplement distributing company, and he said fighting trade barriers while trying to get supplements to farmers before lambing and calving began threatened the success of farmers across the island. McCluggage echoed this. He said that much of the pressure felt under the first months of the Northern Ireland Protocol has been on suppliers.

“There’s a workable solution to all these things,” McCluggage said. “It’s just getting the EU and the UK to agree on it.”

That agreement has appeared more and more distant.

On March 11, a top official of the British Cabinet, Michael Gove, announced Britain would delay new paperwork requirements documenting the health of animal products like meat from April 1 to October. The six-month delay is intended to allow time for NI infrastructure to prepare to meet paperwork requirements. Gove blamed the ongoing COVID pandemic for the move.

“We know now that the disruption caused by COVID has lasted longer and has been deeper than we anticipated,” Gove said. “Accordingly, the government has reviewed these timeframes.”

However, some in Northern Ireland are pointing fingers at the British government for creating the problem. Stephen Farry, a member of parliament from the Alliance Party in Northern Ireland, has called on both sides to cut a deal to ease the movement of food.

“Great Britain is operating with the EU, including Northern Ireland, on essentially [World Trade Organization] rules,” Farry wrote, blaming UK for wanting “autonomy, even though in practice the EU and UK are both keeping similar high standards.”

Although the British decision pushes back some of the immediate issues, farmers and ranchers are weighing options and risks to invest in new markets. Armstrong said a noticeable amount of lamb was being purchased and eaten in NI compared to previous year. The change, which he said is attributable to more people cooking at home during the pandemic, has provided opportunities for Armstrong to distribute lamb at local supermarkets, while Brexit restrictions make relationships with Armstrong’s typical buyers and many supermarkets’ suppliers impractical and uncertain. While this caused beef and lamb prices to rise dramatically, Armstrong still wondered if he was even breaking even, as the bills for rising prices of feed and fertilizer simultaneously accumulated.

However, the UK’s departure from the EU has many anxious for new food policy specific to the region. DAERA Minister Edwin Poots said it could be the “most significant change in policy affecting the agricultural sector in over 40 years.”

With Brexit and COVID in the equation, NI farmers are looking for ways to remedy early trade confusion, while employing policy to help the agriculture sector weather the effects of the pandemic and their new-found autonomy three to five years down the road. Going forward, Alastair said he hopes policy is geared to make local meat more viable, as farmers now look to London instead of Brussels.