Tourists wandering the streets of Belfast now take selfies in front of thick concrete or sturdy metal walls running alongside streets, many of the barricades decorated with bright pops of graffiti or murals.

These “peace walls” started going up in 1969 to separate Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods in an effort to tamp down violence at the dawn of what became known as The Troubles. They were so effective that walls continued to pop up for decades afterward.

Now some 20 miles of “peace walls” run throughout Northern Ireland, a physical reminder of the region’s centuries long history of division.

“We are a society that lives side-by-side and yet in different worlds,” said John Brewer, a social sciences professor from Queen’s University Belfast and research expert on peace processes, religion and conflict. “…So, we have a rather cold peace, in which we no longer kill one another, at least to the same degree, and yet we still live in separate worlds.”

“We are a society that lives side-by-side and yet in different worlds… “ John Brewer, Queens University

For most of the region’s existence there’s been tension between Protestants and Catholics, those who want to remain part of Britain and those who want unity with the Republic of Ireland. When experts and others discuss the Northern Ireland, they say the issues boil down to two colors: orange and green.

Although surveys indicate religion has lost some of its hold on Northern Ireland, the unionist and nationalist division that was once sparked by religious segregation, remains strong.

Experts say these divisions have come to the fore in recent years as tension rises around Brexit and the complex trade agreements and borders between the United Kingdom and European Union. For perhaps the first time since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the question of whether Northern Ireland might rejoin the Republic of Ireland is a hot topic.

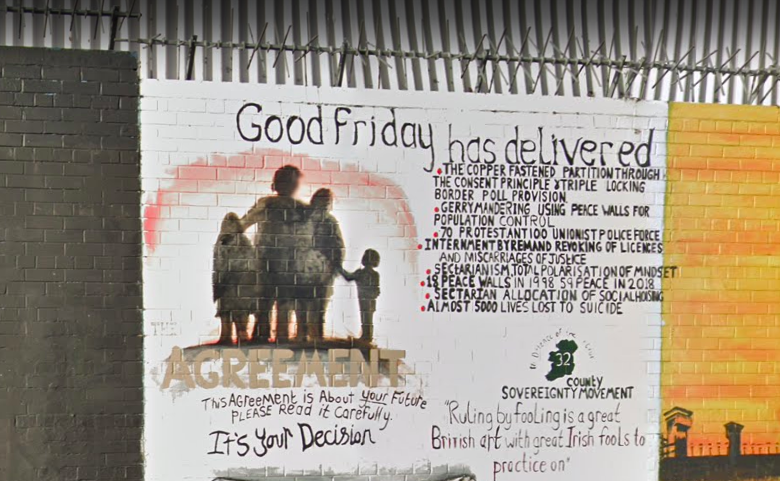

When the Good Friday peace deal ended the 30-year war known as the Troubles, there was hope that perhaps the region would move beyond these old splits. A new generation not mired in the violence of the past and growing up in a world connected through ever expanding social networks would come together as a people.

“There is a narrative, and it’s one of the myths I try to dispel, that there is this post-conflict young generation… and they’ve grown up and stopped caring about the ideological future,” Kevin McNicholl, political science research fellow at the University of Edinburgh, said. “And that’s not the case.”

McNicholl said that on issues “of how unionist or nationalist you are, or whether you want a united Ireland, or whether you want to be a part of Great Britain, or what party you vote for. The youngest people tend to be less centrist.”

McNicholl said his research points to one main factor to explain this: school.

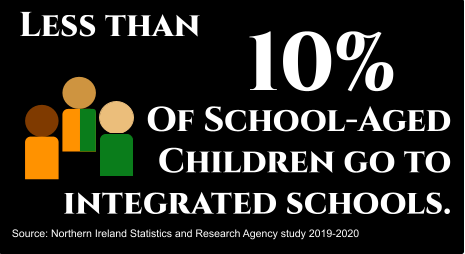

According to Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, less than 10% of school-aged kids in Northern Ireland went to religiously integrated schools during the 2019-2020 academic year.

“Integrated education is not popular in Northern Ireland,” Brewer said. “It’s not popular, for example, with the Catholic church.”

Brewer said the Catholic church wants to teach its kids the ethics of their beliefs, and thus doesn’t like integrated education. Add to this that the public schools have historically been seen as pro-Protestant and it is easy to see why so few schools are truly integrated.

This idea of separation runs deep in the region.

“Segregation is very common in most major cities, be that racial segregation… or segregation between rich and poor,” McNicholl added. “I mean people are surprised and shocked whenever they hear only [10%] of children go to school together, only about 9% of people marry someone of a different religion. But I mean, I also like to say, in other countries is that so different?”

Source: Google Earth

McNicholl’s point rings true. While physical symbols of segregation like the “peace walls” still exist in Northern Ireland, capturing the morbid curiosity of tourists, the United States is still very much segregated based on race, even 50 years after the Civil Rights Act.

A UCLA Civil Rights Project study found that in 2013 around a fifth of all white kids went to a school that was 90% white, while a fifth of all Black kids went to a school that was 90% Black.

So, just as segregation of white and Black kids in American schools fostered division in the U.S., the segregation of Protestant and Catholic school kids fostered division in Northern Ireland.

McNicholl said it is only with time that these divisions feel. He said those with friends of different identities or religions are more likely to take a neutral political stance or identify as Northern Irish, rather than British or Irish.

“It’s only going to university at age 18 or 19 that some of them encounter a member of the other tradition,” Brewer added. “They have separate friendship patterns. They have separate leisure interests.”

“How does religion feed in? It feeds in in every way,” Jennifer Todd, politics and international relations professor at University College Dublin, said.

“How does religion feed in? It feeds in in every way.” Jennifer Todd, University College Dublin

But as central as religion is to Northern Ireland’s version of segregation, it’s undergoing major change.

Todd noted that in the 1970s everyone in Northern Ireland claimed a religion, while now around 20% of the region’s population doesn’t.

But still tension tied to the question of being loyal to Britain or unifying with Ireland has see-sawed for decades. She said political tensions, religion and backgrounds all factor into spikes and dips in the amount of people who claim political identities.

Todd said at the time of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 there were 45% of people who didn’t claim to be nationalist or unionist. That number has gone up and down over the years, spiking in 2018 with 51%, but then dropping to 39% this year.

When political tensions rise Todd said people often go back to their roots saying, “in the end I’m a unionist,” or, “in the end I’m a nationalist.”

Todd said Brexit has pushed people back into their corners, likely accounting for the drop in neutrality this year.

She said a lot of nationalists are aggravated because leaving the European Union is not what they signed up for with the Good Friday Agreement, especially as Ireland remains in the EU. But unionists are also frustrated by a deal that leaves Northern Ireland in an uncertain position, for example with the sea border separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK’s market. As Britain avoided creating a hard border on the island of Ireland, it instead created one through the sea that divides the rest of the UK from Northern Ireland.

“Unionists do not like the Northern Ireland protocol, they’ve tried to get it abolished, British government says, ‘sorry lads, it’s staying,’” Brewer said. “It’s staying because the Northern Ireland protocol allows a free trade agreement with the EU.”

Brewer said the British government doesn’t care about Northern Irish politics, not even the unionists who stay loyal to them. And Todd agreed, adding that it doesn’t care much about nationalist interests either.

“Time and time again, Britain demonstrates to unionists that it’s British interests that matter, not unionist interests,” Brewer said.

Source: Google Earth

But where today’s tensions may lead is far from clear.

The largest nationalist party, Sinn Fein, has called for a border poll, McNicholl said, which would potentially reunite Northern Ireland with the rest of the island, but that could fuel more division in the years to come.

Brewer said he’s been asked over and over by foreign journalists whether or not he believes Brexit will lead to violent conflict.

“I have to say that I think some of them were operating with a rather anti-Irish stereotype which said if the Irish aren’t killing themselves over politics they’ll find something else to kill themselves over: Brexit,” he said.

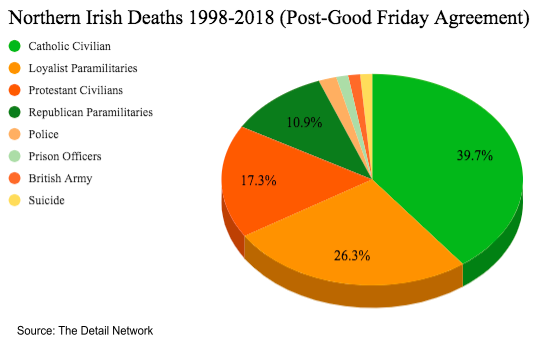

Brewer believed Brexit was unlikely to lead to more conflict, let alone on the scale of the Troubles. Though political tensions have never subsided entirely and there have been occasional sparks of violence, with 158 people killed between 1998 and 2018.

“That’s [158] deaths too many, but in the worst years of the Troubles we would’ve had [158] in two months, not 22 years,” Brewer said.

Just as the “peace walls” still stand, so do the political and religious segregations that have fueled division in Northern Ireland for centuries. Like Brewer, McNicholl said he didn’t think violence would break out like it did during the Troubles, but he said he couldn’t predict the future.

“There are many, many more ‘peace walls’ than there were in 1998,” McNicholl said, adding that expanding on poverty levels remain high and paramilitaries continue to recruit young boys.

“So, there’s cause for concern, but it’s difficult to say for sure. It’s not going to quickly spiral into the ‘70s by the end of the year.”

Just before the 23rd anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, those concerns came to fruition: After months of heat being added to the political tensions over Brexit, it boiled over into conflict.

Throughout the first week of April loyalist demonstrators rioted throughout Belfast and other Northern Irish towns, injuring dozens of police officers, attacking a journalist and setting fires. Many have said the violence is in reaction to Brexit’s Irish Sea border, which could weaken Northern Ireland’s place in the UK.